I didn’t really know Sid Catlett.

But a couple of years ago, I got to spend more than an hour on the phone with him. I’d called him for an interview for something I was working on about D.C. area high school basketball. I’d asked for about 15-20 minutes of his time.

What I got was more than 60 minutes of history, philosophy, reflection, gratitude and thought-provoking observations on learning, life and growing up with the game in Washington, D.C.

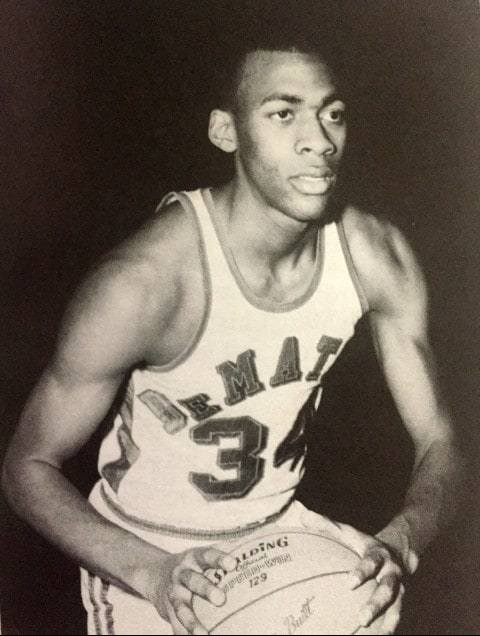

Those who knew Catlett probably aren’t surprised. I, on the other hand, was struck by his gracious, thoughtful nature and his eagerness to talk about his playing days at DeMatha and on the city’s playground courts.

Catlett, like so many basketball-crazy kids who grew up in the D.C. during the early 1960s, learned the game that way. He remembered regularly walking a mile or so from his home in Edgewood to the legendary playground (and proving ground) at Turkey Thicket, where the top players in the city gathered.

He recalled two and three carloads stuffed with players arriving in rapid succession at the courts there, or at Luzon, or even at Chevy Chase, where Boston Celtics coach Red Auerbach sometimes dropped by in the summer.

Many area players in those days – like Catlett – were inspired to work on their game after seeing Elgin Baylor, one of D.C.’s own, playing pro ball for the Lakers on television. Even if you couldn’t make it to the NBA like Baylor, his ascent demonstrated that basketball could mean college, a ticket to something beyond your neighborhood. He’d shown it could be done.

“Baylor, for many of us, was the focal point,” Catlett said. “He was one from our hometown who had done so well. Basketball was not just a game; it was an opportunity to do something no one else in your family had done – to go to college.”

And although Catlett, who played at Notre Dame, understood the long-range implications of basketball excellence, he never lost sight of the joys and beauty of the game at hand. He spoke of how he marveled at the picture-perfect jumper of a Billy Gaskins, the deadly, line-drive shot of a Tom Littles and the stealth-like way in which Austin Carr accumulated all those points. They – and many others at the time – were constantly testing themselves, trying to improve, striving to be the best.

“The competitive spirit at that time was very intense,” he said.

Catlett was fortunate – by his own admission – to have caught the crest of the wave at DeMatha, which was then in the process of becoming the best high school basketball program in the city, if not the country.

“Everyone was gunning for you,” said Catlett, a member of DeMatha’s Class of ’67. “You felt it before games and you felt it on the playgrounds. They were gunning for you because you represented DeMatha. That’s why it was so competitive; that’s why it was so great. Even though the rivalry was great, the camaraderie was great, too.”

But DeMatha – almost always – had an edge. Between 1960 (the end of the great Archbishop Carroll dynasty) and 1976, DeMatha failed to win the title in the highly competitive Catholic League just once, losing out in Catlett’s senior year to Austin Carr-led Mackin. During Catlett’s four years on the varsity, the Stags won three league titles and went 109-9.

And legendary coach Morgan Wootten was the architect. For all Wootten’s strategic acumen, it was his ability to reach people that Catlett remembered most.

“He understood young people and how they could get riled up,” he said. “He just had the ability to keep people cool.”

Catlett was a key figure in DeMatha’s biggest win ever, its upset of Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and Power Memorial in 1965. That DeMatha victory ended the New York City school’s 71-game winning streak in front of 12,500 at the University of Maryland’s Cole Field House.

For the record, Catlett was the leading scorer (13 points) in the Stags’ 46-43 victory. But it was Catlett’s his defense – and Wootten’s tactics – that delivered the upset.

Alcindor scored 35 points in the first meeting between the two teams the year before, which Power won, 65-62. In the rematch, Wootten knew he had to switch gears. He couldn’t afford to let Alcindor go wild like that again.

So, he had his guards pressure the ball, making it hard to get it inside the Alcindor. Wootten also used his three big men – Catlett, Bob Whitmore and Bernard Williams – to deny the seven-footer his favorite spots on the floor whenever possible. They also double-team him whenever he caught the ball in the post. It worked, as Alcindor managed just 16 points, about half his average.

“Depending on where he was, there were always two people on him,” Catlett recalled. “We’d beat him to a spot, take him out of his comfort zone and away from the particular places on the floor he liked. It was not a single person effort by any means. It was a collaborative effort.”